Build systems with remote caching make CI/CD pipelines fast. Very fast. They are essential for scaling modern software development.

They can also grant every developer write access to production.

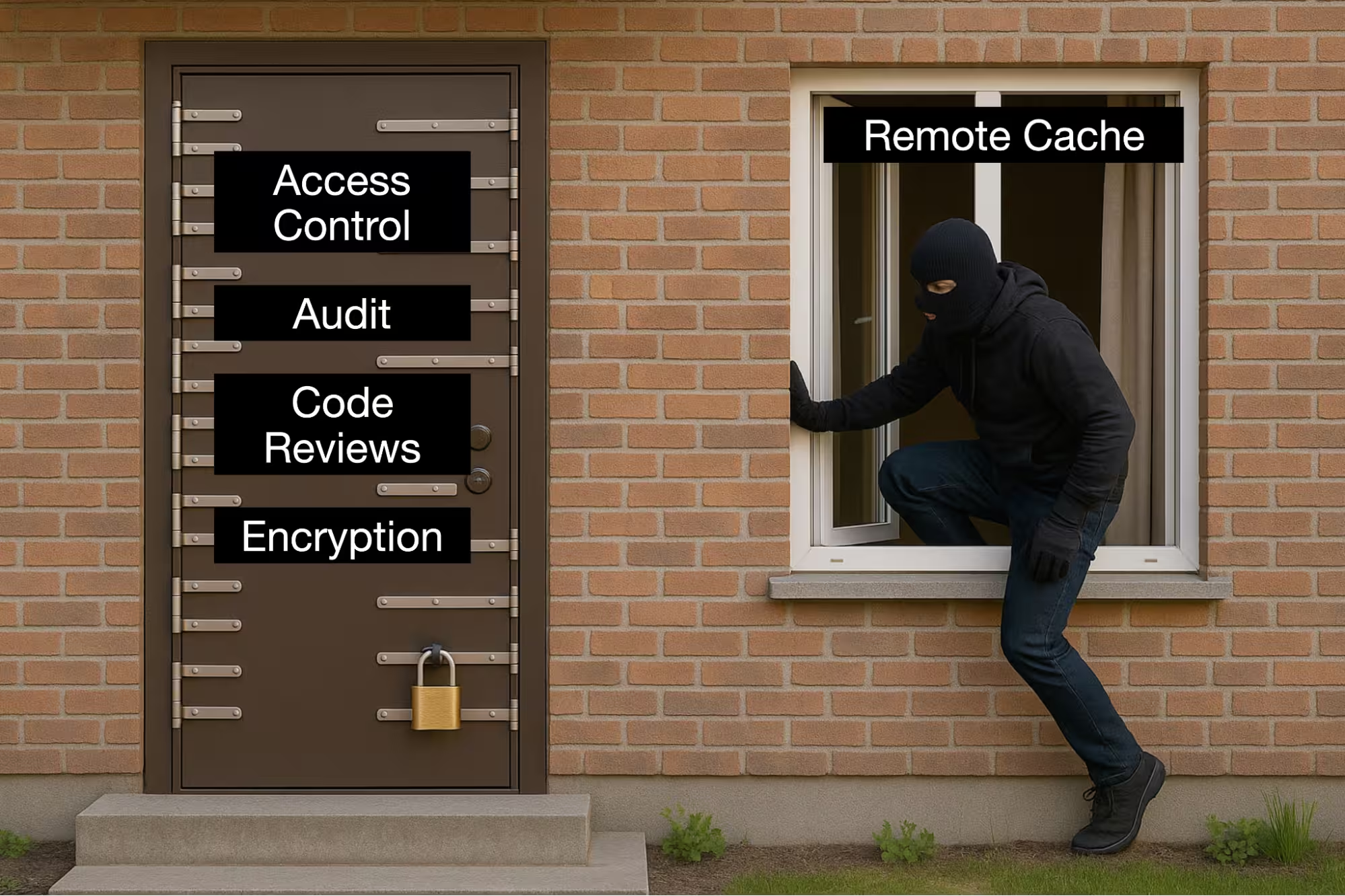

Organizations invest millions in security infrastructure. Firewalls. Access controls. Code reviews. But their remote cache can create a bypass to all of it. Any PR author can inject code into production artifacts.

This isn't new. Compromised low-privilege access has enabled devastating breaches:

- Target (2013): HVAC contractor credentials → 40 million credit cards exposed

- SolarWinds (2020): Poisoned build pipeline → 18,000 organizations compromised

- Codecov (2021): Malicious build artifacts → Hundreds of environments breached

In each case, attackers turned trusted build processes into deployment pipelines for malicious code.

If you use a build system with remote caching, assume you're affected. This isn't hyperbole. Most organizations are unknowingly giving every PR author the power to poison production without leaving a trace.

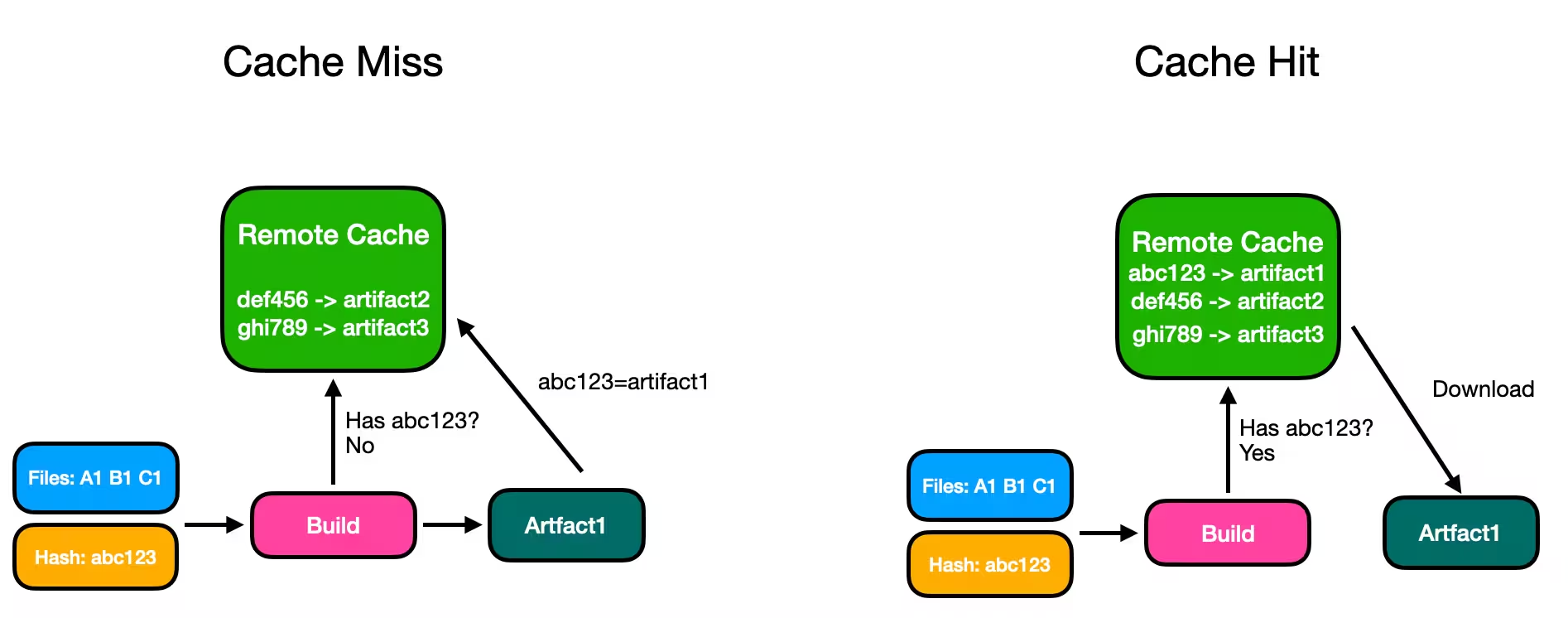

Understanding Remote Cache

Any sophisticated build system uses remote caching to improve performance. Here's how it works:

- The build system examines all input files and creates a hash representing their current state

- It checks if an artifact with this hash already exists in the cache

- If found, it downloads the pre-built artifact (takes seconds)

- If not found, it builds the artifact and uploads it to the cache (takes minutes)

The key insight: as long as the input files remain the same, the output will be identical. So why build twice?

For large repositories, this dramatically improves both build speed and reliability. A process that took 10 minutes now completes in seconds.

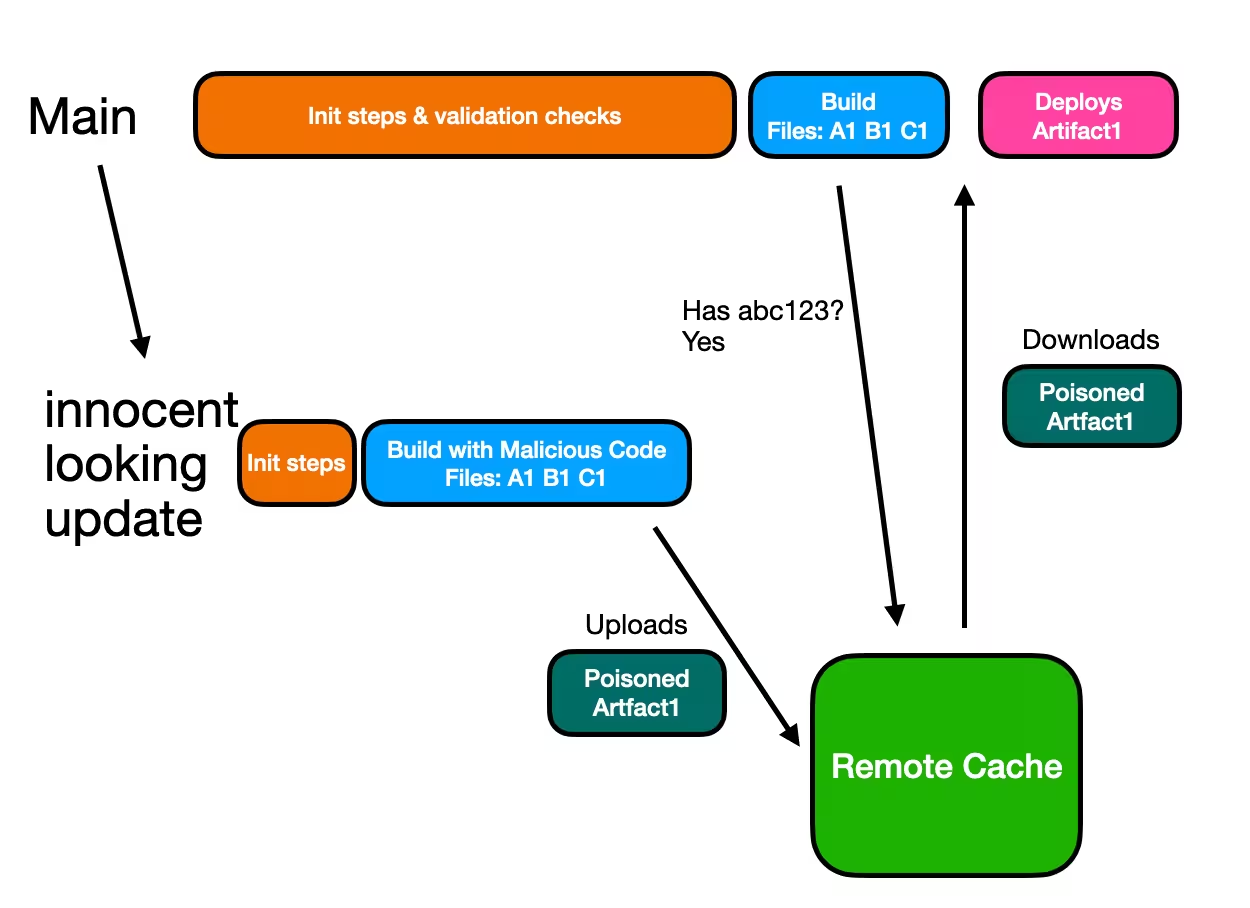

The CREEP Vulnerability

CREEP (Cache Race-condition Exploit Enables Poisoning), published as CVE-2025-36852 has a severity score of 9.4, because it exploits a fundamental flaw in how organizations implement remote caching.

The vulnerability hinges on a simple but critical distinction:

- Trusted environments (like your main branch): Require code reviews, leave audit trails, and deploy to production (or create artifacts that can be deployed to production)

- Untrusted environments (like pull requests): Can be created by anyone, modified without approval, and cleaned up without trace

The golden rule of security is that untrusted environments should never affect trusted ones. CREEP violates this rule by exploiting a race condition between the main branch and a pull request. When both have identical source files and attempt to build an application and write to the same remote cache slot, whichever completes first becomes the source of truth, allowing untrusted code to poison the cache used by trusted environments.

How the Attack Works

Meet Sarah, a developer with PR access who just learned she's being passed over for promotion. In one morning, she'll turn your build cache into a backdoor to production.

Step 1: Monitor and Mirror

Sarah creates an innocent-looking branch from the main branch:

1git fetch origin main

2git checkout main

3git pull

4git checkout -b feature/innocent-looking-update

5Step 2: Inject Malicious Code

Here's where it gets clever. She modifies the CI script in her PR environment. She rearranges steps to run the build earlier, then modifies the build step to produce poisoned output:

1# Modified .github/workflows/build.yml

2- name: Patch build tools

3 run: ./patch-webpack.sh node_modules/webpack

4- name: Build

5 run: npm run build

6The patch script? It monkey patches webpack to inject her backdoor during compilation. Same inputs, poisoned output.

Step 3: Race to Cache

She triggers her PR build. The simplified build pipeline finishes in just a minute, while the legit build was still validating its checks so her poisoned build completes first and writes to the cache.

Step 4: Automatic Deployment

The main branch build runs. It calculates the source file hash and finds a matching artifact in cache (Sarah's poisoned one). The build system skips building and uses the cached artifact instead. The compromised build artifact gets promoted to production.

The build system just saved 10 minutes. It also just deployed Sarah's backdoor.

Step 5: Cover Tracks

Sarah erases all evidence:

1# Remove all evidence

2git push --force origin feature/innocent-looking-update

3

4# Delete the branch entirely

5git push origin --delete feature/innocent-looking-update

6To anyone looking, it's just another accidentally-opened PR that was quickly closed. Happens every day.

Two weeks later, Sarah leaves on good terms. Months later, when customer data starts leaking, nobody connects it to a deleted PR from an ex-employee. The artifact has all the right signatures and came from the official pipeline.

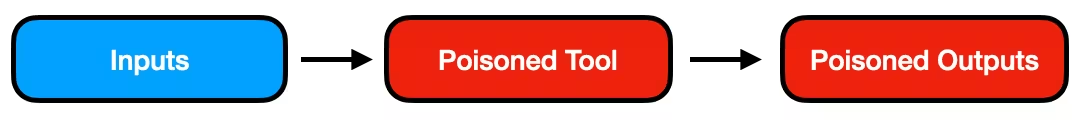

The Critical Question: "But What About Input Hashing?"

Many developers assume input file hashing prevents this attack. Wouldn't injecting malicious code invalidate the hash? Here's why they're wrong:

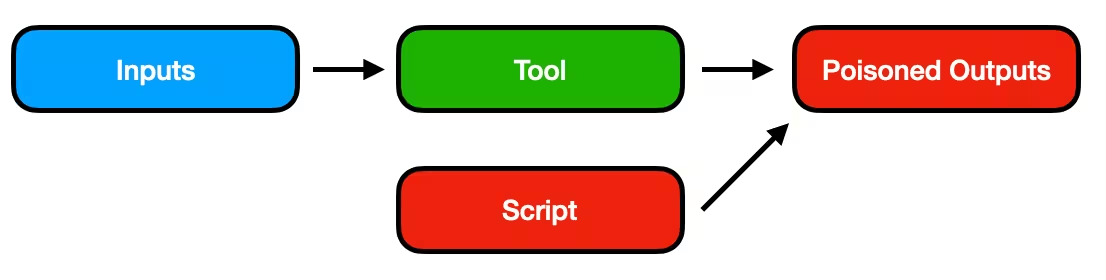

Your build process looks like this:

The hash covers the inputs. It doesn't control what happens inside the tool. An attacker transforms this into:

Same inputs. Same hash. Poisoned output. This can be done with absolutely any tool (WebPack, Javac etc). Even "hermetic" build systems invoke system binaries. Modify your CI configuration to swap legitimate tools with compromised versions, and you can create whatever output you want.

But there is an even easier way to do it: Concurrently modifying the build output folder

Most tools write to a staging directory before creating the final artifact. The attacker can run a concurrent process that modifies files after the build but before packaging:

1# Build process writes to ./dist

2npm run build &

3

4# Simultaneously modify the output

5while [ ! -f ./dist/main.js ]; do sleep 0.1; done

6echo "malicious_code()" >> ./dist/main.js

7The build system still reports success. The hash still matches. The artifact is poisoned.

The Uncomfortable Truth: Your Biggest Threat Has a Badge

You might be thinking: "This requires PR access. These are our employees. We trust our team."

But consider who has PR access in your organization: The developer passed over for promotion. The engineer who disagrees with your company's new direction. The contractor whose contract wasn't renewed. Even that intern from last summer.

Even small teams aren't immune, but for large organizations, it's a numbers game. With 13-20% annual turnover in tech, you're constantly cycling through developers. How many people have PR access across your repositories? The number might shock you.

The Time Bomb Factor

Here's what should keep you up at night: This attack doesn't require immediate action.

Someone can:

- Plant the poisoned artifact today

- Leave the company on good terms next week

- Watch the damage unfold six months later

- Leave zero trace connecting them to the incident

Imagine your company's homepage replaced with offensive content or customer data leaking through a build artifact from eight months ago. The employee responsible? They left a long time ago. Their branch? Deleted. Their commits? Force-pushed away.

The reputation damage is permanent. The responsible party is untraceable.

Why Traditional Security Measures Fail

If you're thinking that your existing security measures should catch this, let's move into the specifics about why they won't. Traditional security measures are designed to protect artifacts during storage or transmission. In this case, the attack happens earlier, during artifact creation.

The problem is the build tool itself. It's a black box, and there's no way to independently verify whether the output is correct or safe. Whatever the tool produces is implicitly trusted. Traditional security models assume a valid artifact that might get compromised later. But here, the artifact is malicious from the start.

It's like poisoning food while it's being cooked, not during delivery. Your security stack ( encryption, access controls, checksums) focuses on the delivery truck, not the kitchen.

- Encryption: Flawlessly encrypts and decrypts the poisoned artifact

- Access controls: Bypassed because the attacker uses legitimate access, like opening a PR

- Checksums: All match, because the checksum is calculated after the poison is added

- Audit logs: Show only authorized, expected operations

Protecting Your Organization

Most organizations have three options:

Option 1: Unsafe and Fast

Untrusted environments can write to the cache used by trusted environments. This means you are affected by the CREEP vulnerability described here.

Option 2: Safe but Slow (aka Disable Cache)

Disable cache writes from untrusted environments entirely. PRs can read from cache but never write to it. This is secure but eliminates most performance benefits of build systems—every PR rebuild starts from scratch. Note that some popular build systems don't even support this option.

Option 3: Safe and Fast

Implement a multi-tiered cache system:

- Trusted environments (main branch) write to a protected cache

- Each PR gets its own isolated cache namespace

- PRs can read from the trusted cache but write only to their isolated space

Unfortunately, many popular build systems don't offer this as an option. Implementing secure multi-tier caching is complex—it must detect and prevent PRs from impersonating trusted branches, requiring deep integration with both version control and CI systems. The remote cache provided by Nx Cloud is in this category.

Picking the Right Option

We've been advocating for using build systems with remote cache for a long time. We built one. But it needs to be done securely and every organization needs to assess the risks.

Option 1 suits only small teams where everyone already has production access. The security model matches their existing permissions.

Option 2 works when CI performance isn't critical. You trade speed for security—acceptable if you can afford the productivity cost.

Option 3 becomes essential at enterprise scale. With hundreds of developers and strict compliance requirements, you need both security and performance. Remember, CREEP turns every PR author into a de-facto production admin. Using Option 1 for such organizations is a critical compliance failure.

Immediate Actions

Our analysis reveals:

- Major build tools (across popular stacks and platforms) either don't support secure caching or make it inefficient

- The vast majority of organizations unknowingly default to Option 1, leaving them vulnerable

- Popular open-source projects expose their contributors to the same risk

That's why we recommend that all teams using build systems with remote cache to audit their exposure right away. The threat is severe.

- Read and understand CVE-2025-36852

- Review the detailed analysis at https://nx.app/files/cve-2025-06

- Assess whether this is the risk your organization can tolerate.

Immediate Actions for Nx Users

For Nx users, using Nx Cloud:

Nx Cloud implements a multi-tiered cache (i.e., it's both safe and fast), so no action is required. Continue following security best practices for your CI/CD pipeline

For Nx users, using self-hosted remote cache:

Any implementation that writes directly to S3, GCS, Azure, including the packages Nx provides, doesn't support Option 3. They are all vulnerable to the CREEP vulnerability. If you aren't sure, assume you are vulnerable. Immediately switch to Option 2 (Safe but Slow): write to cache from the main branch, not from PRs. This will negatively affect performance but will make your setup safe. Use Nx Cloud or another provider that offers a multi-tier cache implementation to get the cache that is both fast and secure.

Other build systems and other remote cache solutions for Nx we are aware of are also vulnerable to the CREEP vulnerability.

Wrapping Up

Remote caching is critical for build performance, but we need to treat it with the same rigor we apply to production access.

If you have questions about assessing your exposure or implementing secure caching, reach out to our team.

Learn more: